Parts of Speech

Nereidic can be analyzed as having three types of word-like units: lexical morphemes, lexemes, and syntactic morphemes. Lexical morphemes generally carry most of the meaning in an utterance and cannot occur independently; instead, some relationship must be established between two lexical morphemes to form a lexeme. Lexical morphemes can be further subdivided into nominal morphemes and verbal morphemes, which perform functions or have meanings similar to that of nouns and verbs. The equivalents of adjectives, adpositions, etc. are all classified as verbal morphemes in Nereidic. Syntactic morphemes occur independently and may not combine with other lexemes. Syntactic morphemes are used to apply syntactic functions to the lexemes that make up an utterance.

Classes and Hierarchies

Human languages often show some sort of coding asymmetry that arises from typicality, represented through the referential scales below. Values for properties toward the left part of the scale are characteristic of referents that typically appear as subjects (such as animate entities), whereas properties on the right side of the scale are characteristic of referents that typically appear as objects (such as inanimate entities). Many languages employ different marking strategies when this typicality is broken, such as differential object marking or differential subject marking. In other words, in languages with the former, direct objects are more likely to be marked when they have properties that typical of sentential subjects, while languages with the latter are more likely to mark subjects when they have properties typical of sentential objects.

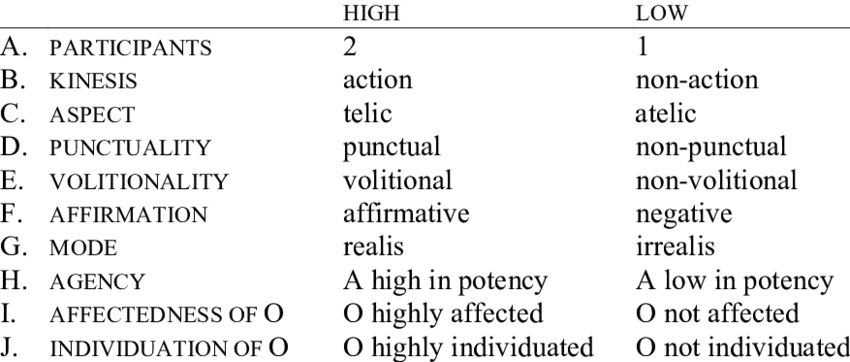

Somewhat related is the concept of transitivity, a property of clauses, which can be broken down into several parameters addressing features of the subject, verb, and object of the clause. The table below summarizes the different parameters that affect transitivity, properties of high transitivity on the left and properties of low transitivity on the right. Differences in the transitivity of a clause can cause a wide variety of patterns and grammatical manifestations in human languages, varying from the types of marking core arguments receive to the presence of special verbal morphology.

Nereidic culture, social behaviors, and biology are characterized by a strict caste system, a reverence for appendages and radial symmetry, and a highly distributed nervous system. Crucially, the number of appendages and, consequentially, the number of lines of symmetry a nereid has, the more they are typically revered as intelligent or wise and the higher their status in society. Because of this, notions of typicality and transitivity are conflated in most Nereidic languages with notions of appendages, symmetry, and hierarchies. In Standard Nereidic specifically, this has resulted in four nominal morpheme classes and four verbal morpheme classes. The nominal morpheme classes are roughly determined by the number of appendages, appendage-like structures, or lines of symmetry the referent has; the more limbs and lines of symmetry, the more animate the class behaves, while the less limbs and less lines of symmetry, the less animate the class behaves. Verbal morpheme classes, on the other hand, are tied directly to the level of transitivity of the action. The respective classes of nominal and verbal morphemes heavily determine how the morphemes interact and combine as lexemes, and the type of grammar that is used to mark dependencies between them. For example, a sedecimal class nominal morpheme as the subject of a sedecimal class verbal morpheme will manifest as a strong dependency (i.e., more fusionally derived lexeme), while a binary class nominal morpheme as the subject of a sedecimal class verbal morpheme will manifest as a very weak dependency (i.e., less fusionally derived lexeme). The various nominal and verbal morpheme classes and their properties are outlined below:

Nominal Morpheme Classes:

- Sedecimal Class: personal pronouns, multilimbed organisms and objects, circular objects, etc.

- Octal Class: organisms and objects with eight or more limb-like structures, octagonal objects, etc.

- Quaternal Class: insects, tetrapods, objects with four~six limb-like structures, rectangular objects

- Binary Class: fish, worms, snakes, thin or line-like objects, etc.

Verbal Morpheme Classes:

- Sedecimal Class: highly transitive verbs, the direct object is heavily affected or destroyed

- Octal Class: low transitive verbs, the direct object is partially affected or not affected at all

- Quaternal Class: intransitive action verbs, unergative verbs (some degree of volitionality involved)

- Binary Class: unaccusative verbs, stative verbs, etc.

Lexemes and Head-Foot Dependencies

The primary driving force of deriving Nereidic lexemes is what is known as “head-foot dependencies.” Essentially, every lexeme in Nereidic is a combination of at least two lexical morphemes that form a dependency with each other, one being the head and the other the foot. The exact nature of this dependency and how it is formed in the grammar depends on the class of the morpheme employed. Typically, the higher the rank of the morpheme in the hierarchy, the more it acts as a head and will attract or “control” morphemes lower in the hierarchy; and likewise, morphemes lower in the hierarchy will act more as a foot and be attracted to or “controlled” by morphemes higher in the hierarchy.

For example, if we take the four nominal morphemes, hnnarq (nereid / ‘person’; class: sedecimal), zur (spider; class: octal), yirx (chair; class: quaternal), and siex (string; class: binary), and combine them with the octal class verb nir (to touch), the following combinations are produced if the noun is the agent:

- narqhnnir (nereid touches)

- nurzir (spider touches)

- yirxnir (chair touches)

- nir siex (string touches)

And if the noun is the patient, the following combinations are produced:

- nir a-hnnarq (nereid is touched)

- nir a-zur (spider is touched)

- nir yirx (chair is touched)

- siexnir (string is touched)

There are four types of morphological manifestations of the dependencies depending on the hierarchies of the lexical morphemes, their relationship, and how unexpected the relationship is. The more expected or natural the relationship, the stronger the dependency and the more the two morphemes are incorporated into one another to form a lexeme; the less natural the relationship, the more distant the morphemes and less incorporated. The following outlines the four different morphological dependencies:

- Full Incorporation: the morphemes are compounded and swap onsets.

(i.e. A(hnnarq) + nir > narqhnnir) - Partial Incorporation: the morphemes are simply compounded and cannot appear separated.

(i.e. A(yirx) + nir > yirxnir) - Unmarked Separation: the morphemes are unbound with no marking present, dislocation is possible.

(i.e. P(yirx) + nir > nir yirx) - Marked Separation: the words are unbound, the foot is marked by the prefix <a->, dislocation is possible and often preferred.

(i.e. P(hnnarq) + nir > nir a-hnnarq)

If a morpheme is incorporated, then it cannot take on other dependencies; instead, other relations must be established using syntactic morphemes. If, however, the morpheme is unbound (has a weak connection to its head or foot), then it can form other dependencies. For example, if we use the word from before, we can make two complete transitive sentences to demonstrate this:

- narqhnnir siexnir ye (the nereid touches the string) – morphemes are bound, ye is used to establish a syntactic relation.

- narqhnnir a-zur (the nereid touches the spider) – a-zur is unbound and can establish a syntactic relation with narqhnnir without a syntactic morpheme.

The following table outlines the incorporation/separation dependency patterns for each verb-noun class combination:

| V16 | V8 | V4 | V2 | ||

| N16 | A | [NV](ω⇄ω) | [NV](ω⇄ω) | [NV](ω⇄ω) | [NV](ω⇄ω) |

| P | [V][N'] | [V][N'] | - | - | |

| N8 | A | [NV] | [NV](ω⇄ω) | [NV](ω⇄ω) | [NV](ω⇄ω) |

| P | [V][N] | [V][N'] | - | - | |

| N4 | A | [N][V] | [NV] | [NV](ω⇄ω) | [NV](ω⇄ω) |

| P | [NV] | [V][N] | - | - | |

| N2 | A | [N][V'] | [N][V] | [NV] | [NV](ω⇄ω) |

| P | [NV](ω⇄ω) | [NV] | - | - | |

- [ ] signifies a distinct word or lexical unit ([NV] = incorporated, [N][V] = separated)

- (ω⇄ω) signifies the onsets are swapped

- [X’] signifies that the word is marked

When a dependency is formed between nominal morpheme pairs, it can have two interpretations depending on the classes of the nominal morpheme and the marking involved: source or goal. The source relationship marks motion away from something, ownership or composition, and instrumentality, while the goal relationship marks motion to something, transfer of ownership, and benefactivity. For example, the following phrases demonstrate the source dependency and goal dependency between two nominal morphemes (hnnarq of class N16 and siex of class N2) and how they might be interpreted:

- sarqhnniex (head: hnnarq; relation: source) – “the nereid of (the) string”

possible interpretations:- “the nereid made of string”

- “the nereid from a place called String“

- “the nereid who is notable for having or using (the) string” (most typical for N16-2 relation)

- hnnarq a-siex (head: hnnarq; relation: goal) – “the nereid for (the) string”

possible interpretations:- “the nereid to be exchanged for string”

- “the nereid who supports the notion of strings”

- “the nereid who desires string” (most typical for N16-2 relation)

- hnniexsarq (head: siex; relation: source) – “the string of (the) nereid”

possible interpretations:- “the string that belongs to the nereid” (most typical for N2-16 relation)

- “the string made out of nereids”

- “the string originating from a place called Nereid“

- siex a-hnnarq (head: siex; relation: goal) – “the string for (the) nereid”

possible interpretations:- “the string to be given or sent to a nereid” (most typical for N2-16 relation)

- “the string made for the benefit of a nereid”

The following table outlines the incorporation/separation dependency patterns for each nominal morpheme pair class combination. It should be noted that, just like the verb-noun combinations, the head always precedes the foot:

| Foot→ Head↓ | N16 | N8 | N4 | N2 | |

| N16 | S | [N][N'] | [N][N] | [NN] | [NN](ω⇄ω) |

| G | [NN](ω⇄ω) | [NN] | [N][N] | [N][N'] | |

| N8 | S | [N][N] | [NN] | [NN](ω⇄ω) | [NN](ω⇄ω) |

| G | [NN] | [N][N] | [N][N'] | [N][N'] | |

| N4 | S | [NN] | [NN](ω⇄ω) | [NN](ω⇄ω) | [NN](ω⇄ω) |

| G | [N][N] | [N][N'] | [N][N'] | [N][N'] | |

| N2 | S | [NN](ω⇄ω) | [NN](ω⇄ω) | [NN](ω⇄ω) | [NN](ω⇄ω) |

| G | [N][N'] | [N][N'] | [N][N'] | [N][N'] | |

Apart from the use of syntactic morphemes (which will be discussed in a later section), this head-foot dependency forms the basic building blocks of Nereidic phrases and sentences. In other words, sentences and phrases are formed through combining verb-noun and noun-noun combinations that are held together through head-foot dependencies.

Bubble Syntax: Pop, Merge, and Submerge

Nereid syntax – i.e., the combination of lexemes (morphemes connected through head-foot dependencies) to form constituents – is fundamentally different from human syntax and is best understood through a system called bubble syntax. A bubble represents a syntactic constituent—a complete syntactic unit. Bubble syntax operates as a stack-based grammar (first in, last out) organized around the concept of a bubble discourse, an infinite stack of bubbles that collectively form a discourse.

In this framework, bubbles encapsulate the semantic core or content of the discourse, with lexemes (as defined earlier) being the simplest type of bubble. The bubble discourse can be visualized as a linear sequence of bubbles, where only the top bubble is accessible at any given time. As new bubbles are added, older ones are pushed deeper into the stack. Syntactic morphemes, in turn, apply operations to the top bubble in the discourse.

There are three primary types of syntactic morphemes (or bubble operations): pop, merge, and submerge.

Pop functions remove the top bubble from the discourse, interpreting it as a complete utterance that is no longer accessible or relevant. For example, consider the bubbles: [nereid eats], [seaweed eaten]. When stacked into the discourse as “[nereid eats] [seaweed eaten]”, applying a pop function removes [seaweed eaten] and interprets it as the complete utterance: “the seaweed (was) eaten.” The remaining bubble [nereid eats] can then be popped to yield the separate utterance: “the nereid ate.” It’s important to note that these two utterances are independent—the seaweed in the first bubble and the object of the nereid’s eating in the second are not necessarily the same. In speech, this sequence might look like: “[nereid eats] [seaweed eaten] ᴘᴏᴘ ᴘᴏᴘ”.

Merge functions combine two or more bubbles into a larger bubble, establishing a relationship between their contents. For instance, merging [nereid eats] and [seaweed eaten] produces a composite bubble: [[nereid eats] [seaweed eaten] ᴍᴇʀɢᴇ]. If this merged bubble is then popped, the resulting interpretation might be: “the nereid ate seaweed.” Here, the merge function creates a relational structure where “eating” links the contents of both bubbles.

Submerge functions push the top bubble deeper into the discourse, making another bubble accessible for manipulation. For example, in the sequence [nereid eats] [seaweed eaten], applying a submerge function to [seaweed eaten] pushes it below [nereid eats]. This allows [nereid eats] to become the accessible bubble for further operations. A sequence like “[nereid eats] [seaweed eaten] ꜱᴜʙᴍᴇʀɢᴇ ᴘᴏᴘ” would yield the interpretation: “the nereid ate,” leaving [seaweed eaten] in the discourse as incomplete.

Each type of bubble operation—pop, merge, and submerge—can vary in complexity depending on:

- The number of bubbles affected or accessed from the discourse stack.

- Formality and register of speech.

- Modal or contextual information conveyed.

Syntactic Morphemes: Negation, Modality, etc.

First Order Operations:

Second Order Operations:

Third Order Operations: